At the inaugural La Feria Latinx print media fair in New York City last weekend, I couldn’t always hear the artists speak — but that wasn’t necessarily a bad thing.

Selena’s “Amor Prohibido” blasted across one floor in a New York University (NYU) building on Manhattan’s Cooper Square, later followed by Shakira and Prince Royce’s duet “Deja Vu.” The artists featured in those two songs alone span four countries: the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Colombia, and the United States.

Organized by NYU’s Latinx Project, La Feria featured art, books, posters, stickers, and more by at least 30 artists, whose offerings were as richly varied as the fair’s playlist.

Prices ranged from $1 prints by the Queens-based Mobile Print Power collective to over $100 for each of Gabriel García Román’s Queer Icon prints.

“I’ve never been to one of these fairs,” Panamanian-American artist Nicoletta Daríta de la Brown said. “But I love it, because this is like a bodega: Yeah, come take something with you.”

De la Brown, whose booth was titled “Botánica Bodega,” sold large mesh bags reading: “I learned how to love and heal in my Abuelita’s kitchen.” The works are meant to be used as real grocery bags, inspired by the artist’s memories of shopping with her abuela. Her entire booth, she said, is in memory of her grandmother.

Exhibiting ceramic tiles from Columbus, Ohio, social worker Christian Casas doesn’t make art for art’s sake. Casas picked up art while enrolled in graduate school and now runs ceramics classes for children resettling in the US after crossing the southern border.

“I wanted to make an object to explore ceramics, but also explore their feelings,” Casas said, noting that art can be especially meditative while “new Americans” struggle to translate from language to language in their daily lives.

Also showing at the fair were Les Lopez and Inuer Pichardo, who met in the third grade. The South Bronx duo said they reconnected after some years to document the place where they grew up through “changes,” like increasing housing developments and gentrification.

“My mom always said you stop time by taking pictures. And I think the idea of this was to do just that, and just capture it,” Lopez explained.

Francisco Donoso’s table turned heads, featuring prints of manipulated documentation from his Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival (DACA) proceedings. Donoso said he’s working on a 10-by-20-foot (~3-by-6-meter) painting overlaying these legal documents, but for the fair, he wanted to make them into a book.

“We have to save all that documentation,” he said. “I have boxes of my stuff … I started scanning them and then printing them over my own paintings to create these layers of meaning.”

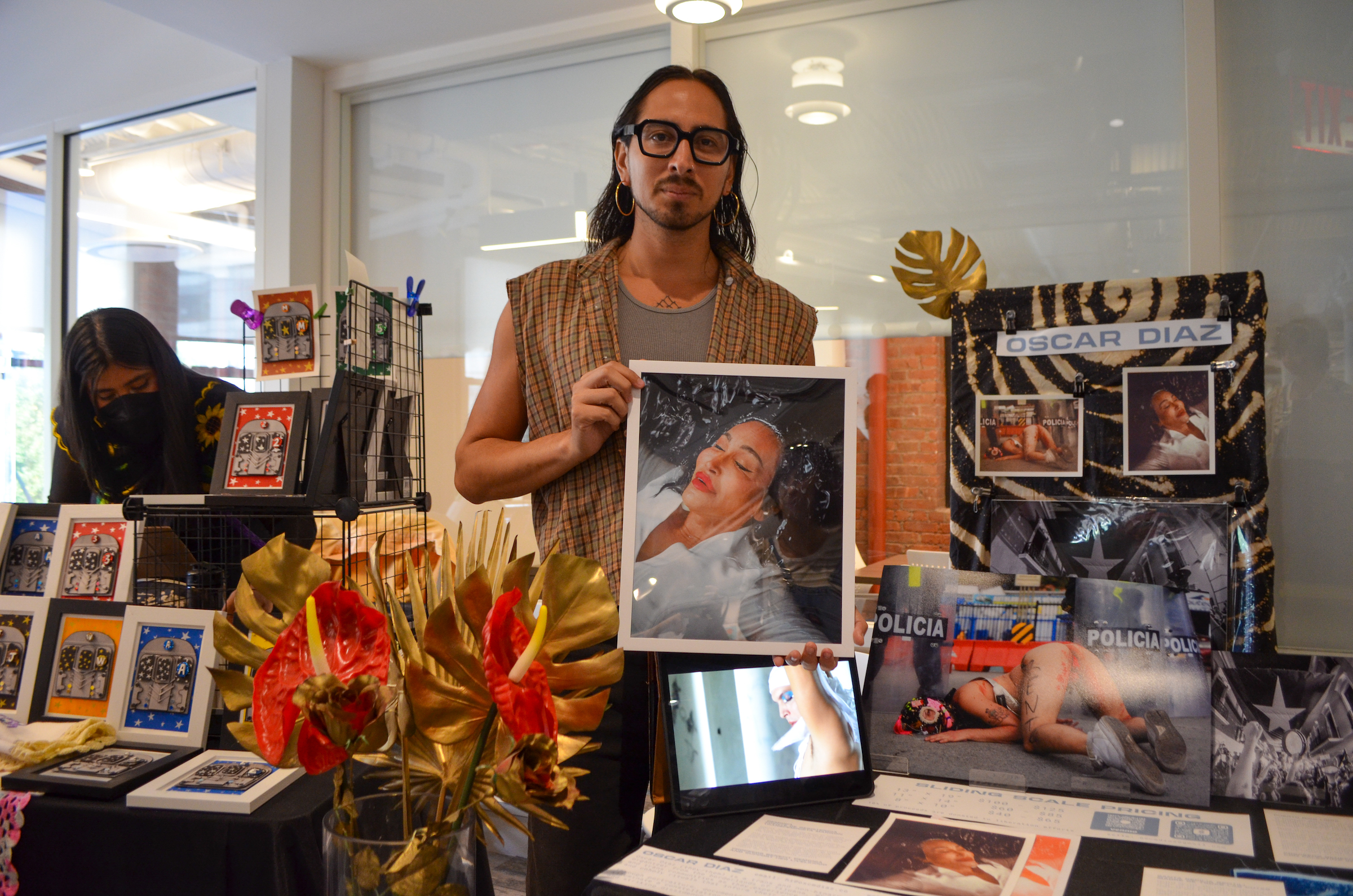

At one of the last tables I visited, Oscar Diaz told me about photographing the late Cecilia Gentili, an Argentinian-American trans activist who the artist said was “half of Brooklyn’s mother.” Months before Gentili’s death in February, Diaz photographed her in “a baptism shoot.” Over 1,000 people attended a ceremony in her memory at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, where she became the first transgender person to receive a funeral mass at the historic church.

“She was the first person that people connected with when trying to access gender-affirming care. If they needed hormones or testosterone starting that journey, she would help,” Diaz said.

In a smaller display, Jessica Elena Aquino sold prints made from carved school erasers, drawing on her background as a teaching artist. She also makes cyanotypes of the landscape in her hometown Santa Ana, California. Her friend seated next to her was eager to tell me that Aquino is also bound for a residency at the University of Arkansas to work with corn husks.

Aquino said the artists easily switched between Spanish and English while speaking with one another, creating a refreshing environment. “You don’t see it all the time, especially in one room,” she added. “I feel more like myself.”