Strewn about a dark room are objects that recall the wreckage of a plane. As I investigated the scene of the catastrophe, I saw cloth bags holding battered metal beams and headlights or, even more ominously, nothing at all, their mouths frozen open like gaping voids. Glowing forms resembling melted milk cartons provide the only light source. The beaded tan-and-black carpet, made of interlocking carseat covers, rattled and slid unnervingly underfoot, crunching like protesting snow. At the center of the disaster is something that recalls an impromptu streetside shrine composed of a lone shoe, a gold watch, a hanging Guanyin charm, and cast epoxy-resin molds of coffee cup lids illuminated like candles. Amid these items is a metal badge that reads “Licensed Taxicab.”

Kenneth Tam’s exhibition The Medallion at Bridget Donahue takes up the devastation of those whose lives have been shattered by the plummeting value of the medallion, a permit to operate a taxi that is unique to New York City. Marketed by the Bloomberg administration as a way to “own a piece of New York,” these medallions seemed like a way to achieve the American Dream; more than half of those who scrimped, saved, and went into debt to attain them are immigrants. Once worth about $1 million each, rideshare companies like Uber and Lyft sent values careening; in 2021, they were worth around $80,000 apiece.

On the far side of the room is the kind of wide-format screen that sits atop a taxicab. The title “Dissolved personal archive (2015–2024)” (2025) suggests that the images in this fast-moving slideshow are drawn from life — I spotted parks, galleries, domestic settings, even personal details like what I thought were backpacks branded with the Center for Art, Care, and Alliances logo — but a closer look reveals them as AI-generated. In each slide, the human figures disappear into Refik Anadol-esque plumes of digital vortices; one generated figure seemed almost to resist this disintegration, staggering a few steps before collapsing. The message is clear — tides of technology wielded for personal enrichment rather than societal improvement will obliterate us with cold ease. Nonetheless, the experience is unsettling.

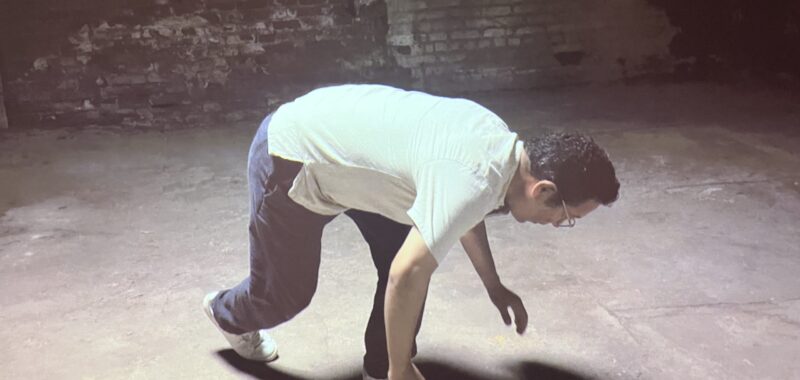

The two-channel video “The Medallion” (2025), projected on opposite walls, continues this critique more elegiacally. In some shots, people contort their bodies as if swept into a slow-motion tragedy; in others, they are submerged, struggling toward a light-saturated surface, as if reaching for salvation. In this submarine context, the word “medallion” takes on an almost mystical connotation, suggesting sunken treasure or pirates’ booty. Of course, taxi medallions were just about as valuable, vaunted, and rare, until they weren’t.

The projected video also features a close-up interview with a man who poured his savings into acquiring a medallion before they hemorrhaged in value. It kept him up at night, he said; the debt, the interest had him flipping from one side of the bed to the other. On the floor in front of the video is “Anxiety Clock” (2025), a patch of those carseat beads rigged up to glow red and flash between random numbers and nonsense symbols, like a hellish DMV where your number will never show.

Kenneth Tam: The Medallion continues at Bridget Donahue (99 Bowery, Lower East Side, Manhattan) through March 8. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.