Benj Edwards / Flux

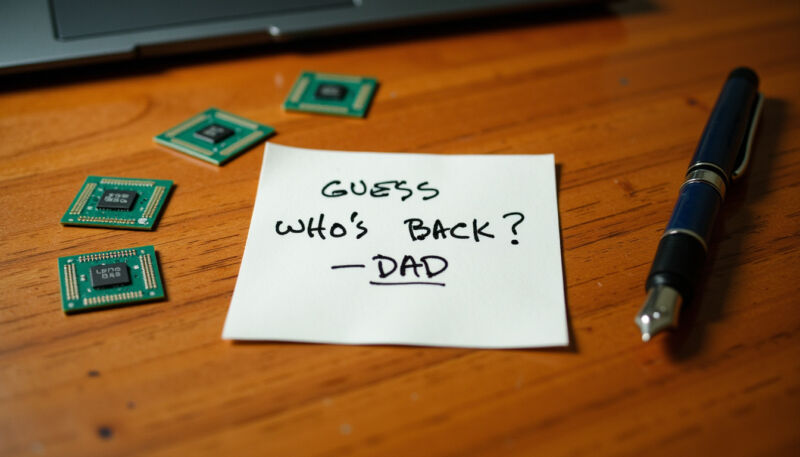

Growing up, if I wanted to experiment with something technical, my dad made it happen. We shared dozens of tech adventures together, but those adventures were cut short when he died of cancer in 2013. Thanks to a new AI image generator, it turns out that my dad and I still have one more adventure to go.

Recently, an anonymous AI hobbyist discovered that an image synthesis model called Flux can reproduce someone’s handwriting very accurately if specially trained to do so. I decided to experiment with the technique using written journals my dad left behind. The results astounded me and raised deep questions about ethics, the authenticity of media artifacts, and the personal meaning behind handwriting itself.

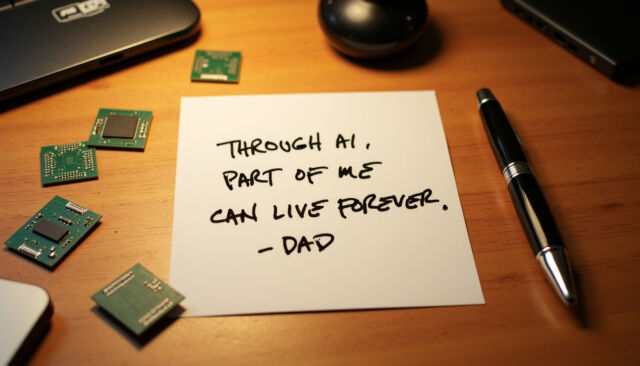

Beyond that, I’m also happy that I get to see my dad’s handwriting again. Captured by a neural network, part of him will live on in a dynamic way that was impossible a decade ago. It’s been a while since he died, and I am no longer grieving. From my perspective, this is a celebration of something great about my dad—reviving the distinct way he wrote and what that conveys about who he was.

Benj Edwards / Flux

I admit that copying someone’s handwriting so convincingly could bring dangers. I’ve been warning for years about an upcoming era where digital media creation and mimicry is completely and effortlessly fluid, but it’s still wild to see something that feels like magic work for the first time. It’s tempting to say we’re stepping into a new world where all forms of media cannot be trusted, but in fact, we’re being given further proof of what was always the case: Recorded media has no intrinsic truthfulness, and we’ve always judged the credibility of information from the reputation of the messenger.

This fluidity in media creation is perfectly exemplified by Flux’s approach to handwriting synthesis. One of the most interesting things about the Flux solution is that the resulting handwriting is dynamic. For the most part, no two letters are rendered in exactly the same way. A neural network like the one that drives Flux is a huge web of probabilities and approximations, so the imperfect flow of handwriting is an ideal match. Also, unlike a font in a word processor, you can natively insert the handwriting into AI-generated scenes, such as signs, cartoons, billboards, chalkboards, TV images, and much more.

-

An AI-generated image using Flux and “Dad’s Uppercase” with the prompt: A pen-and-ink cartoon newspaper tabby cat holding a large ring, showing a word bubble above his head that reads: “Why shouldn’t I keep it?”

Benj Edwards / Flux -

An AI-generated image using Flux and “Dad’s Uppercase” with the prompt “a muscular barbarian with weapons beside a CRT television set, cinematic, 8K, studio lighting. The screen reads ‘ARS TECHNICA.’”

Benj Edwards / Flux -

An AI-generated image using Flux and “Dad’s Uppercase” featuring the prompt “a photo of colorful large billboard beside a highway that reads: ‘THIS IS A RATHER LARGE SIGN'”

Benj Edwards / Flux -

An AI-generated image using Flux and “Dad’s Uppercase” featuring my favorite store, Dadio Shack.

Benj Edwards / Flux -

An AI-generated image using Flux and “Dad’s Uppercase” showing a tattoo.

Benj Edwards / Flux -

An AI-generated image using Flux and “Dad’s Uppercase” featuring a fictional cartoon family.

Benj Edwards / Flux -

An AI-generated image using Flux and “Dad’s Uppercase” showing a chalkboard with fictional Pokemon stats.

Benj Edwards / Flux -

An AI-generated image using Flux and “Dad’s Uppercase” featuring the prompt “a photo of a vintage green computer CRT screen glowing in the dark. You see an Apple II keyboard below the screen. Glowing white on the screen are the graphics ‘APPLE II FOREVER'”

Benj Edwards / Flux -

An AI-generated image using Flux and “Dad’s Uppercase.”

Benj Edwards / Flux

It’s worth noting that neither I nor the person who recently discovered that Flux can reproduce penmanship were the first to use neural networks to clone handwriting—research into that extends back years—but it has recently become almost trivially inexpensive to do so using either a cloud service or consumer-level hardware if you have the writing samples on hand.

Here’s how I brought a piece of my dad back to life.

The discovery

As a daily tech news writer, I keep an eye on the latest innovations in AI image generation. Late last month while browsing Reddit, I noticed a post from an AI imagery hobbyist who goes by the name “fofr”—pronounced “Foffer,” he told me, so let’s call him that for convenience. Foffer announced that he had replicated J.R.R. Tolkien’s handwriting using scans found in archives online.

Foffer initially made the Tolkien model available for others to use, but he voluntarily took it down two days later when he began to worry about people misusing it to create handwriting in the style of J.R.R. Tolkien. But the handwriting-cloning technique he discovered was now public knowledge.

-

A screenshot of the original J.R.R. Tolkien handwriting LoRA before its creator took it down in late August 2024.

Replicate -

An AI-generated image created by a Redditor using Flux and a special model trained on J.R.R. Tolkien’s handwriting.

fofr / Flux -

An AI-generated image created using Flux and a special model trained on J.R.R. Tolkien’s handwriting.

fofr / Flux -

An AI-generated image created using Flux and a special model trained on J.R.R. Tolkien’s handwriting.

fofr / Flux -

An AI-generated image created using Flux and a special model trained on J.R.R. Tolkien’s handwriting.

fofr / Flux -

An AI-generated image created using Flux and a special model trained on J.R.R. Tolkien’s handwriting.

fofr / Flux