For most people, an extinct species is an abstraction, a set of bones they might have seen on display in a museum. For Gennady Boeskorov, they are things he has interacted with directly, studying their fur, their skin, their internal organs—experiencing these animals much as they existed thousands of years ago. Some of the well-preserved Pleistocene animals he has worked with include the mummified remains of woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius), an extinct form of rabbit (Lepus tanaiticus), and cave lion cubs (Panthera spelaea).

His latest paper also makes it clear that woolly rhinoceroses belong on this list. Boeskorov is a senior researcher at the Diamond and Precious Metals Geology Institute, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, as well as a professor at the North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk. This July, he and his colleagues described the relatively recent discovery of three woolly rhinoceros mummies, one of which is new to science, in a paper published in the journal Doklady Earth Sciences.

Woolly rhinos (Coelodonta antiquitatis) were stocky, long-haired, two-horned denizens that inhabited Eurasia during the Pleistocene, a period that includes the most recent glacial expansion. They coexisted with woolly mammoths, placing second on the list of largest animals in this ecosystem (behind their tusked proboscidean coevals), and shared a similar dense coat of hair to protect against the cold.

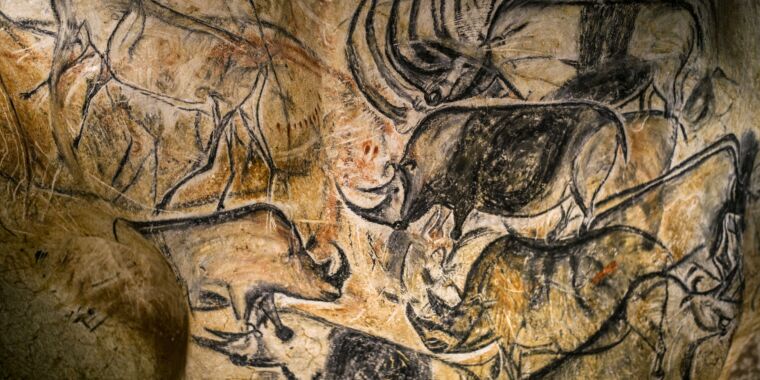

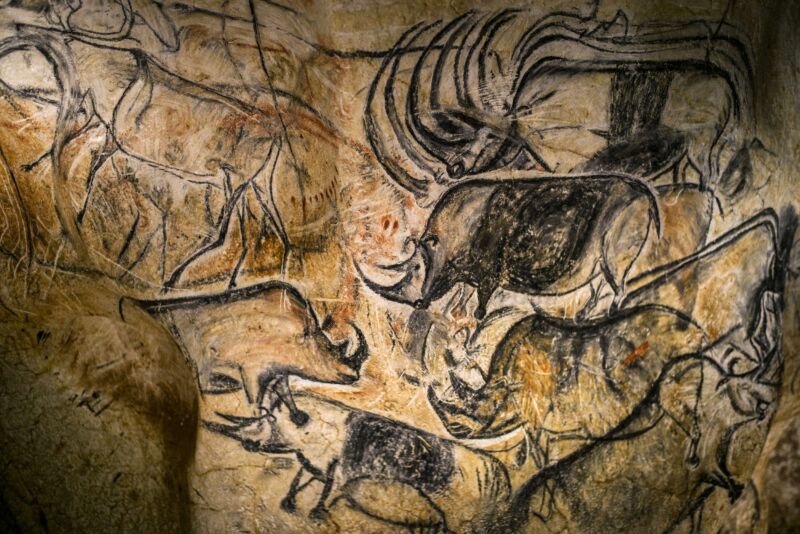

We’ve learned a great deal from their bones; we’re learning even more thanks to their mummies. Being able to directly observe their hair and skin, for example, offers more evidence regarding just how well-adapted these animals were to their harsh environment. And the preservation of soft tissue has allowed us to test a hypothesis that was based on a combination of the organization of their skeletons and depictions in cave art.

Woolly rhino fossils are abundant, but their mummies are exceedingly rare. To date, there have only been a handful of nearly complete woolly rhinos (although news of another has been recently announced). The three mummies in this paper all hail from Yakutia—also known as the Sakha Republic—in northeastern Russia, but they are vastly different in age and preservation.

A trio of finds

Sasha is the first complete baby woolly rhino ever discovered. Although missing about half of its body, it is arguably the most well-preserved of the three, maintaining its fluffy little strawberry-blonde head, a couple of legs, and much of its fluffy torso. The loss of its lower half prevents determination of its sex, but Sasha was between 12 and 18 months old when it died, based on its teeth and the sutures within its skull as seen through CT scans.

So Sasha might have still been nursing at the time of death. Wear on its frontal horn—the second horn following the one above its nose—may have been caused by “rubbing against its mother’s belly” as it nursed, scientists suggested in 2015. The mummy was found in 2014 along the banks of a river, and although the cause of death has yet to be determined, sediment in its nasal passages indicate drowning in mud.

By contrast, the newest mummy is missing much of one side of its body, including most of the intestines—the result of predation, according to the authors. The other side, however, preserves skin, some hair, and soft tissues. Nicknamed the “Abyisky rhinoceros” for its discovery in Yakutia’s Abyisky District in 2020, it is estimated to be a juvenile of about 4 to 4.5 years. This mummy was also found along the banks of a river and, just like Sasha, its sex hasn’t been determined.

Clues to its age, however, were found among the animal’s overall height, its skull bones, and the length and characteristics of its nasal horn (the horn that grows right above its nostrils). Like tree rings or the rings found in mammoth tusks, the number of transverse stripes on the outside of nasal horns indicates the animal’s age. The Abyisky mummy has little surviving hair; tufts of it appear in bits and pieces. The manner of death remains a mystery, but arthropod remnants in its hair indicate that its carcass spent time in a small body of fresh water.

Both the oldest at the time of her death and the oldest in terms of discovery, the Kolyma mummy was uncovered in 2007 in a Kolyma gold mine. The position in which her body was found—her legs pressed to her torso and her head stretched upward—indicates she fell into and was trapped within a confined space. Like the Abyisky mummy, she is well-preserved on one side of her body, but she was not preserved whole. Her horns and legs were found nearby. Her skeletonized head—once joined to the body—was separated when she was excavated from the sediment. Her hair is preserved in tufts.

An udder and nipples are among the anatomical evidence that this is a female. The transverse stripes on her horn, along with teeth, skull, and height, confirm her age at death was approximately 20 years. Spores and pollen within her preserved stomach confirm what was deduced by previous studies of woolly rhino teeth: They enjoyed an herbivorous diet of grasses, shrubs, and numerous other plants.