Amid news coverage of the 2023 Women’s World Cup, researchers with Harvard’s GenderSci Lab spotted a familiar narrative concerning rampant ACL tears.

There was an immediate attribution of women athletes’ disproportionately high injury rates to biological sex differences, remembered Sarah S. Richardson, Aramont Professor of the History of Science and professor of studies of women, gender, and sexuality. “Do women’s hormonal cycles mean that their ligaments are more likely to tear? Does their hip structure mean that their knees are not meant for a certain level of activity?”

In a new study in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, Richardson and her co-authors cast doubt upon explanations that rely solely on sex-linked biology. The researchers specifically homed in on “athlete-exposures,” a metric widely used in the field of sports science — and repeated without question by many journalists covering women’s higher rates of ACL injury. The popular measure embeds bias into the science, the researchers say, because it fails to account for different resources allotted to male and female athletes. They find women may face a greater risk of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury because they play on smaller teams and spend a greater share of time in active competition.

“We knew from previous research that the real story is usually a complex entanglement of social factors with biology,” said Richardson, who founded the GenderSci Lab in 2018. “Our goal was to elevate the consideration that social factors can contribute to these disparities — and to show that it matters quantitatively in the numbers.”

Sports science literature reviewed by the research team included a recent meta-analysis, which arrived at an ACL injury rate 1.7 times higher for female athletes. Most of the 58 studies cited by the meta-analysis calculated athlete-exposures rather simply: the number of athletes on a given team multiplied by total number of games and practices. Exposure was rarely calculated at the individual level. Nor was weight given to time spent in active competition, when injuries are up to 10 times likelier to occur.

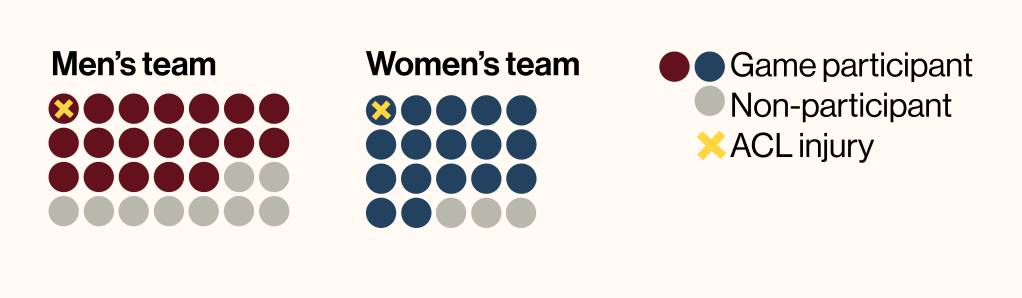

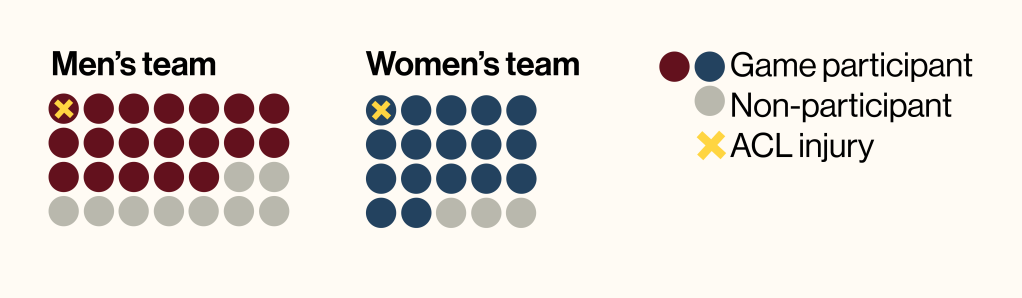

Example of the impact of men’s and women’s ice hockey roster size on calculated exposure time, injury rate, and injury risk. This figure represents one men’s and one women’s team participating in one 60-minute ice hockey match, in which six players per team are allowed on the ice at a given time and unlimited substitutions are allowed.

Source: Limitations of athlete-exposures as a construct for comparisons of injury rates by gender/sex: a narrative review, British Journal of Sports Medicine

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| Roster size-based AEs | 28 | 25 |

| Participant-based AEs | 19 | 17 |

| Player-hours | 6 | 6 |

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| Injury rate per 100 roster-based AEs | 3.6 | 4.0 |

| Injury rate per 100 participant-based AEs | 5.3 | 5.9 |

| Injury rate per 100 player-hours | 16.7 | 16.7 |

| Injury risk per team member | 0.036 | 0.040 |

| Injury risk per participant | 0.053 | 0.059 |

A systematic analysis revealed the folly of this approach. “For every match that a team plays, a women’s team will, on average, train less compared to men,” explained co-author Ann Caroline Danielsen, a Ph.D. candidate studying social epidemiology at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “This is significant not only because injuries are more likely to happen during matches. It’s also true that optimal conditioning helps prevent injuries from happening in the first place.”

Underinvestment in women’s sports also means lower rates of participation, with playing time distributed among smaller numbers of athletes. “If you look at one individual woman ice hockey player, for example, her risk of injury is going to be larger than a man who’s playing on a much larger team,” noted Annika Gompers ’18, a former Crimson runner now pursuing her Ph.D. in epidemiology at Emory University. “At the same time, the actual rate of injury per unit of game time is exactly the same.”

Recommendations for more accurately calculating ACL injury risk include careful considerations of structural factors. “We wish, for example, there was more systematic data on inequities in the quality of facilities,” said Gompers, noting the high-profile example of the NCAA’s 2021 March Madness basketball tournament. Also helpful would be better numbers on each player’s access to physical therapists, massage therapists, and coaching staff.

Sarah S. Richardson (left), Annika Gompers, and Ann Caroline Danielsen.

Photo by Dylan Goodman

But the co-authors also call for improving the very metric used to calculate ACL injury rates. That means disaggregating practice time from game time and specifying each player’s training-to-competition ratio. It means gauging athlete-exposures at the individual level. It also means controlling for team size.

The paper is the first in the GenderSci Lab’s Sex in Motion initiative, a new research program promising thorough investigations into how sex-related variables interact with social gendered variables to produce different outcomes in musculoskeletal health. Its fourth co-author is U.K. sports sociologist Sheree Bekker, who led a 2021 paper that called for greater attention to social inequities in approaching ACL injury prevention.

“There’s a deep story here, and a nice case study, of how gender can be built into the very measures that we use in biomedicine,” Richardson said. “If the athlete-exposures construct is obscuring or even effacing those gendered structures, we’re not able to accurately perceive the places for intervention — and individuals are not able to accurately perceive their level of risk.”

[ad_2]

Source link