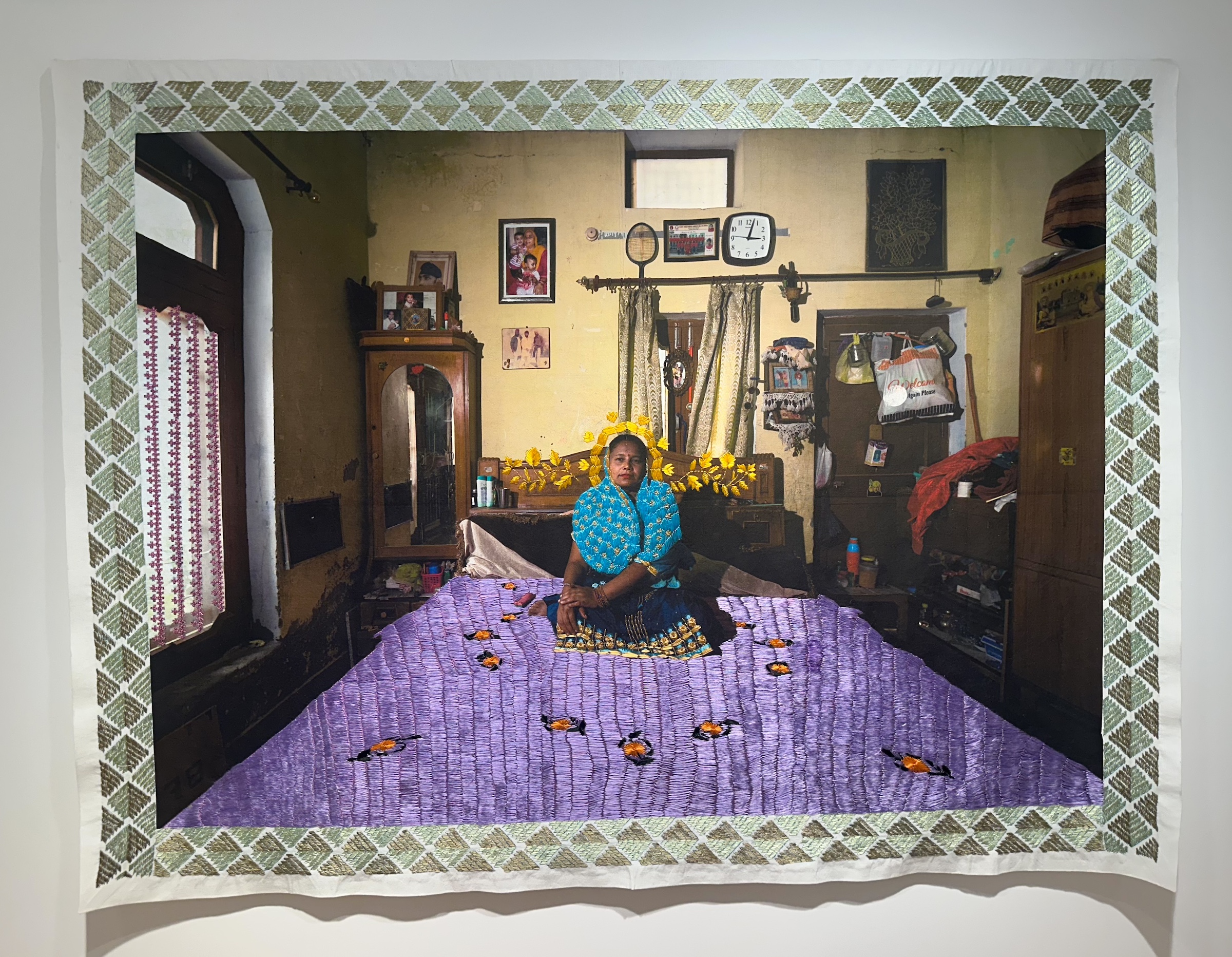

In Jāḷī—Meshes of Resistance, nine embroidered textiles bear photographs of women who gaze out at the viewer and one another. Details sing and delight: folded hands resting on a patchwork of flowers, a dupatta threaded with cyan and gold, droplet-sized mirrors reflecting light. It’s through these lovingly sewn stitches that an unassuming white-walled room at Robert Mann Gallery becomes an intimate home for an unusual show.

New York-based artist Spandita Malik spent two years interviewing and photographing the women who appear in the exhibition, all survivors of domestic violence whom she met through nonprofits in North India. Each was photographed in her own home — the same space where abuse persists and women’s labor is often devalued — but determined her own pose and gaze in a reclamation of agency.

After transferring the photograph onto a locally sourced khadi textile, Malik returned the piece to the sitter, inviting her to embroider her image however she pleased and compensating her for her work. Some sewed over their faces or cut them out entirely, while others crowned themselves in a maze of running stitches or adorned their bedspread with a field of purple thread. Each artist also left traces of her hand in the form of faint fold lines and ink marks, tender residues of process and human touch. By the end of the exhibition, I remained convinced that the gallery should have done more to emphasize that Jāḷī is a group show, rather than a solo one.

Against the grain of a country and world that punishes and denies dignity to survivors, Malik’s show is more than a mere embellishment or reclamation. Her invitation made way for a collective transformation, one in which each artist restitches the fabric of domestic space in the image of her inner world.

I traced this thread of resistance in three techniques, whose stitches linger in my mind’s eye. I keep thinking about the latticed windows in “Jamila Bhegam” (2025), for one. Malik photographed Bhegam sitting on a plastic chair in an open-air space. She, in turn, extended the lattice pattern from the window into the backdrop, embroidering a complex web with herself front and center — gaze direct and hands clasped in self-assurance. Jāḷī, which refers to both latticed screens found on windows across South Asia and traditional mesh stitches, gives the show its name.

Next, Malik photographed “Farhana” (2023) in a dim hallway with green light filtering through a window above. Farhana then places herself at the center of a shimmering golden mesh of classic motifs using metallic gota patti embroidery, typically reserved for formalwear. She tugs at the thread of South Asian textile art, of which women have been at the forefront, and asserts herself worthy of finery in her everyday life.

And in “Heena” (2025), a woman stands beside pots and pans near a brick wall. At her feet blooms a bed of flowers with winking mirrors at their center, a shisha embroidery technique. But if we look for her face, we instead find our own, reflected back to us in another mirror bordered with thread. Just as Malik invited her, Heena invites me — and you — to find glints of ourselves in these portraits of other people.

Jāḷī—Meshes of Resistance continues at Robert Mann Gallery (508 West 26th Street, Suite 9F, Chelsea, Manhattan) by appointment only through June 28. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.