Today, much of the visual communication around public health is digital — in Instagram infographics, TikToks, or YouTube videos. But in decades past, posters, printed out and pasted up in public, were a key way to spread messaging.

“People remember information better if it’s presented both visually and with printed messages,” said Amanda Yarnell, chair of the Chan Center for Health Communication, which helps online creators spread evidence-based health messages in ways that resonate. “Seeing something and reading something at the same time improves understanding.”

Harvard University has digitized more than 3,000 posters related to a single major public health crisis: the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The posters come from numerous countries around the world and span roughly 1990 to 2004. The collection tells a story, said Yarnell, of what the public health establishment has learned about what messages work, and why.

Message, feeling, action

In the small area of a poster — and the limited time in which you might hope to catch someone’s attention — designers need to craft a single simple message. Too many words and you lose people.

“A good poster is one point and a feeling: something that the messenger wants you to remember, and then the feeling helps you remember it,” said Yarnell, who is also the Dependent Lecturer on Social and Behavioral Sciences at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “And best-case scenario, there’s a route to more. It used to be a phone number, and then it became a website, and now it’s probably a QR code.”

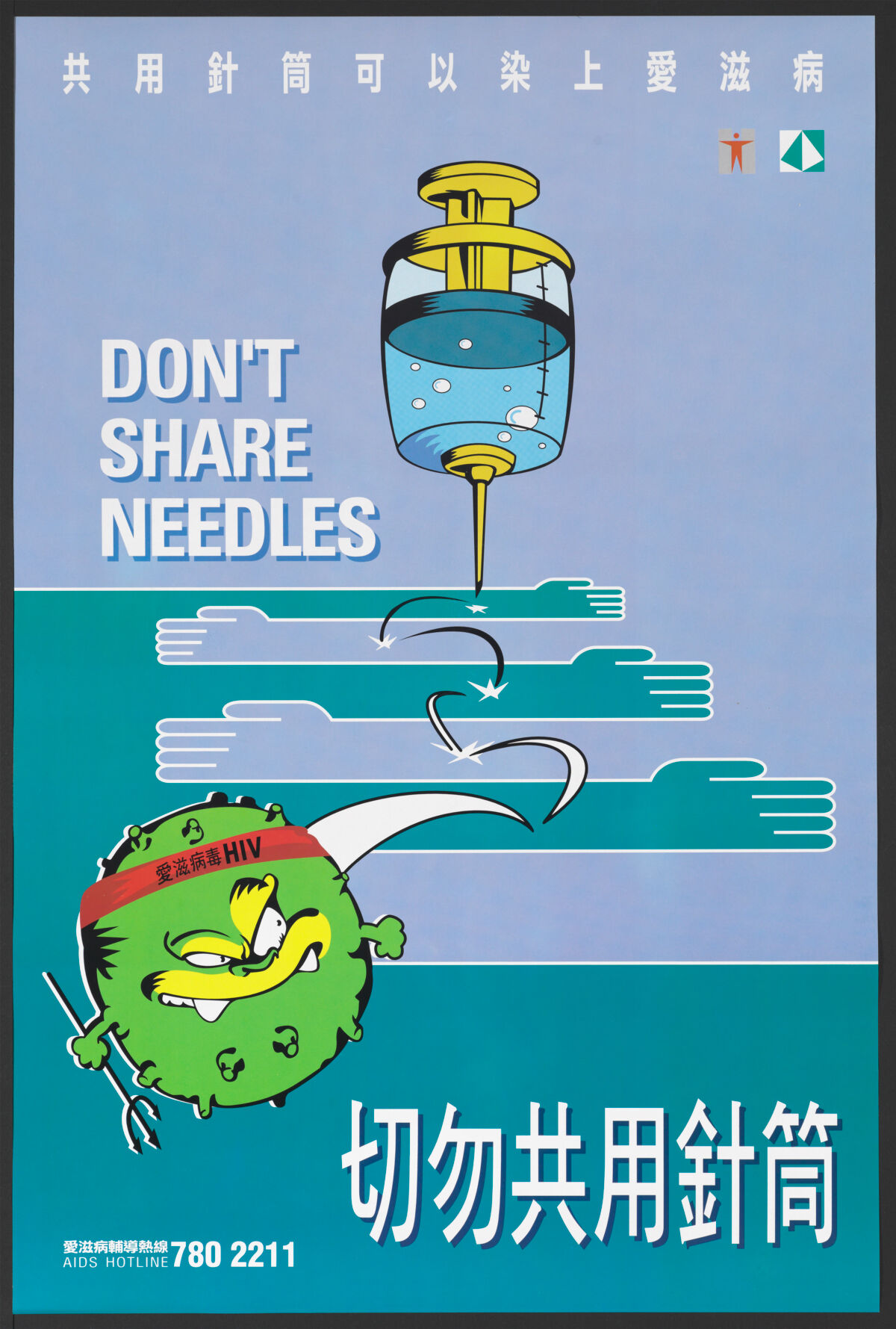

China.

Harvard University, Collection Development Department. Widener Library. HCL, W542995_1

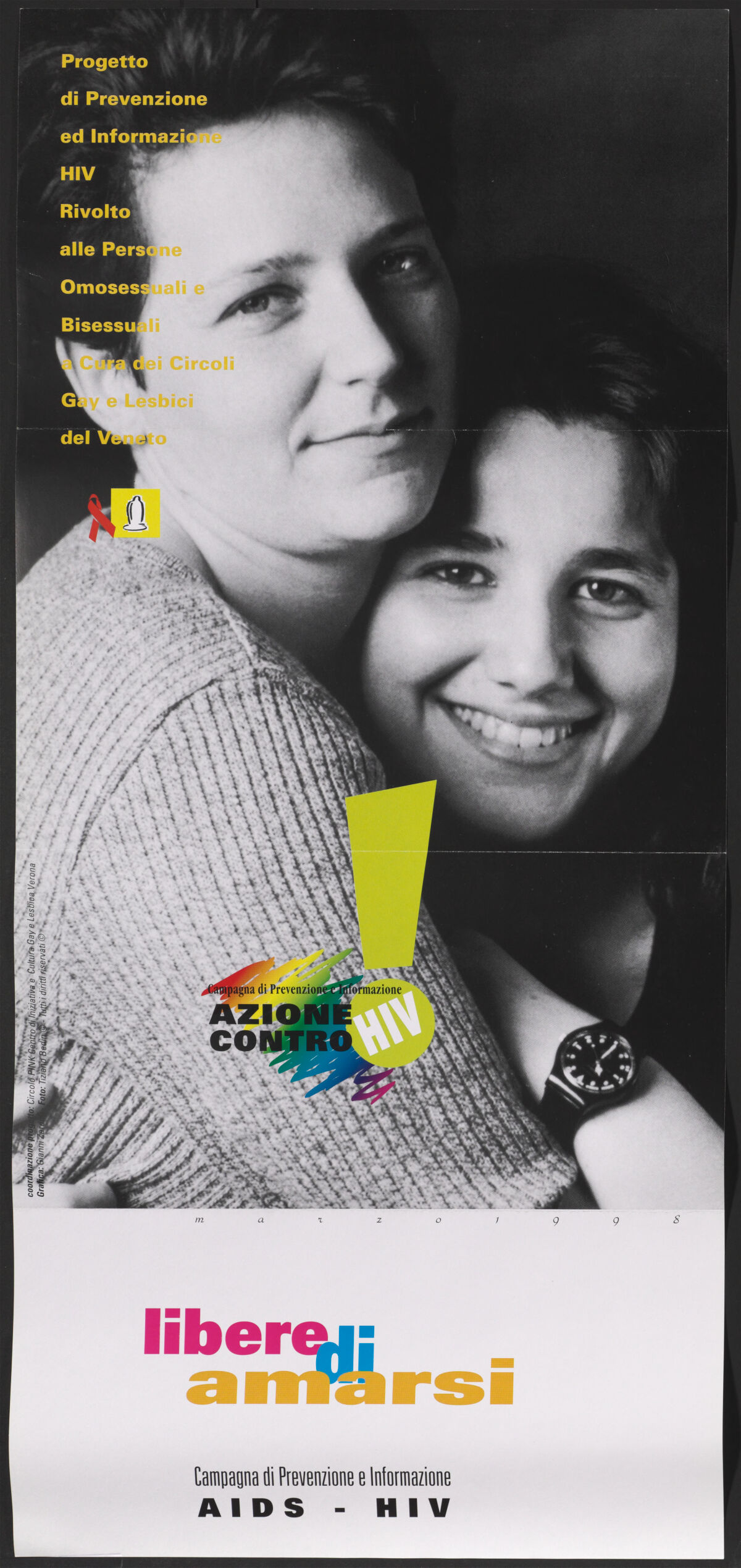

Italy.

Harvard University, Collection Development Department. Widener Library. HCL, W539985_1

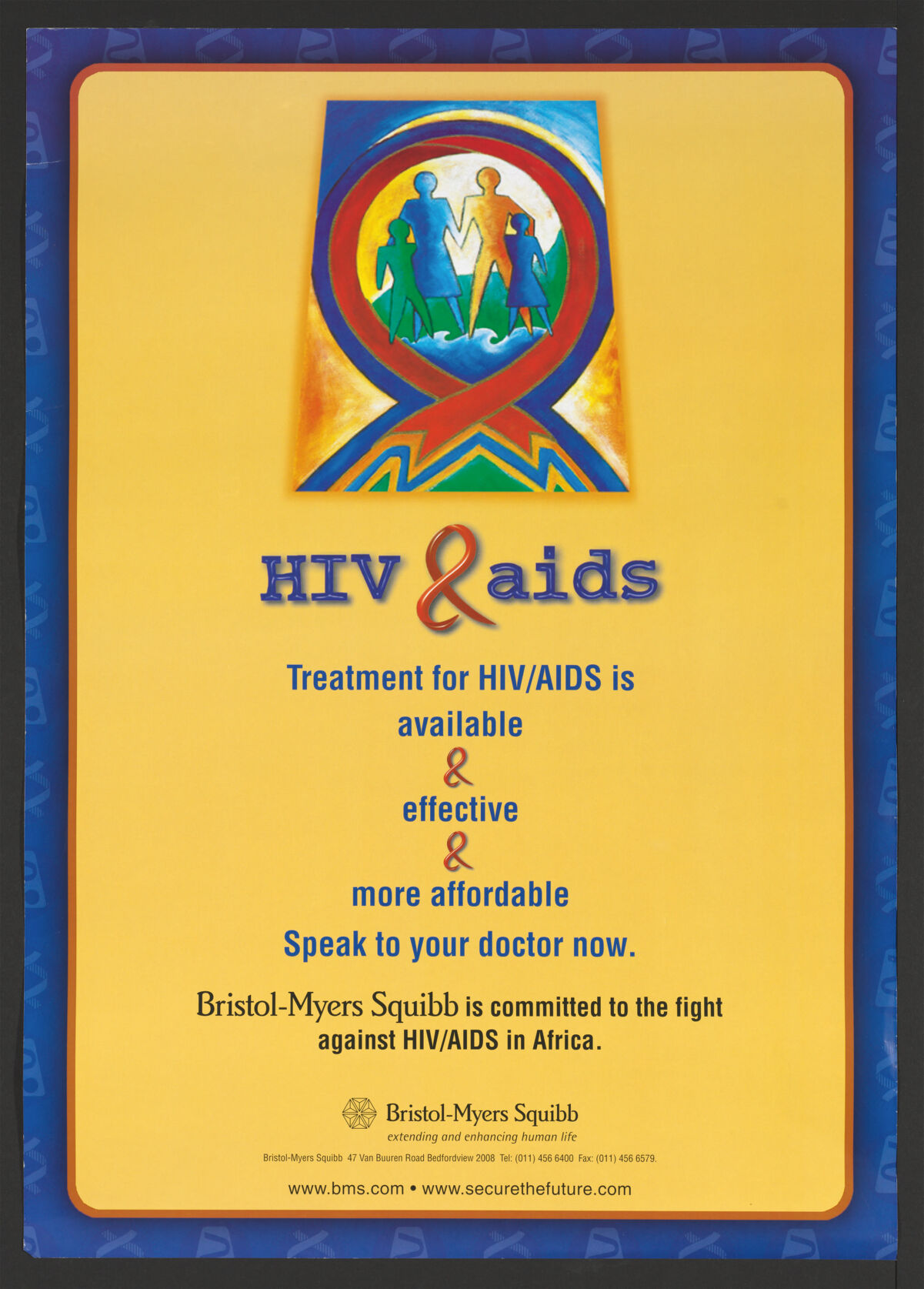

South Africa.

Harvard University, Collection Development Department. Widener Library. HCL, W548279_1

Canada.

Harvard University, Collection Development Department. Widener Library. HCL, W463584_1

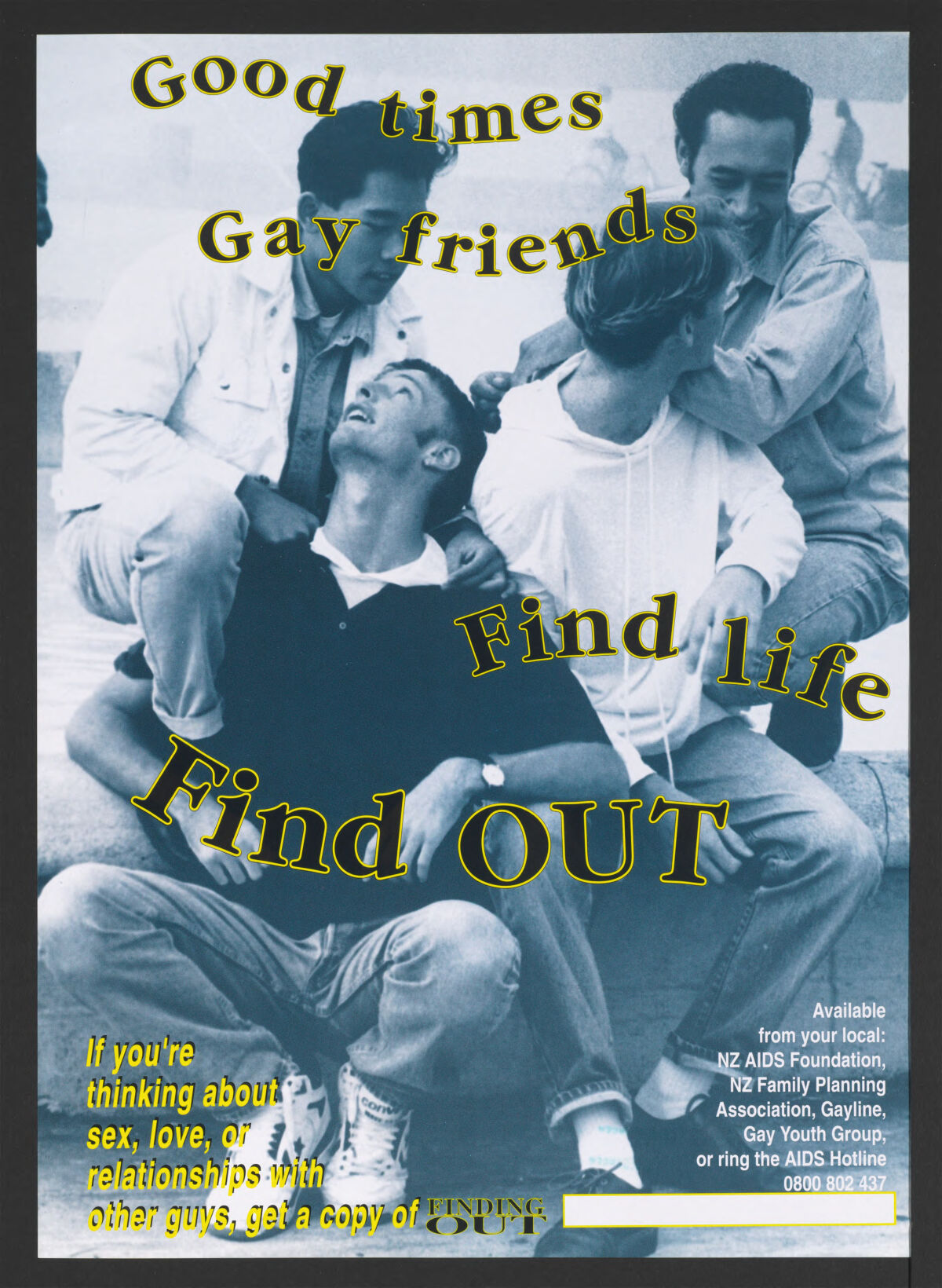

New Zealand.

Harvard University, Collection Development Department. Widener Library. HCL, W547869_1

Go big

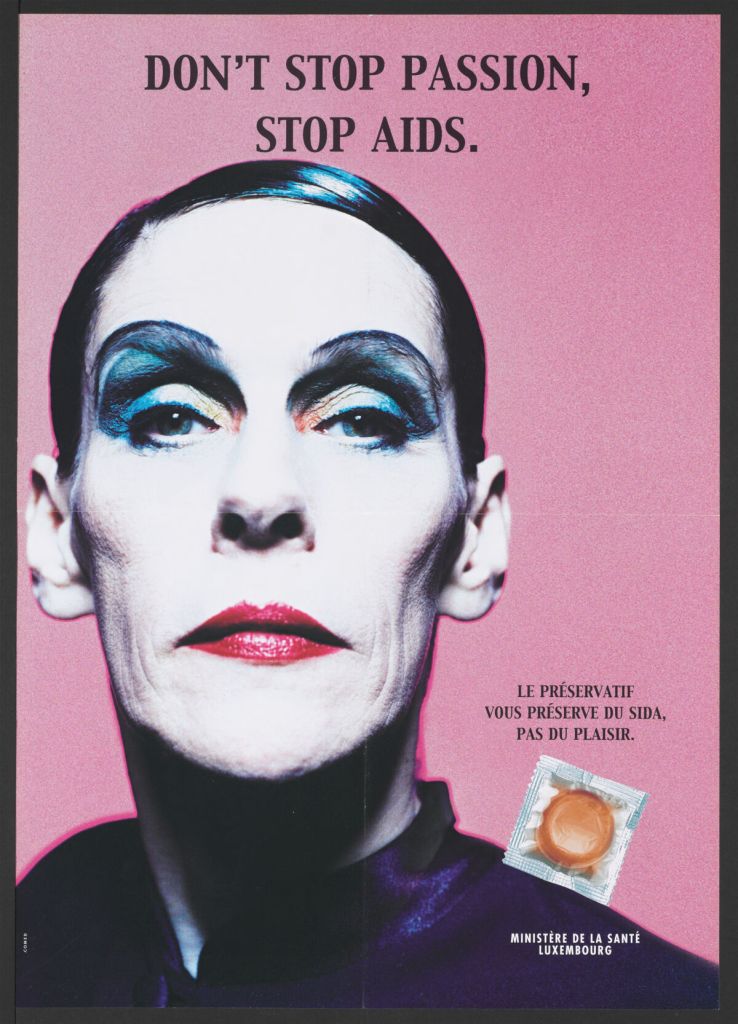

Effective messages can be bold, eye-catching, or even provocative.

“Something that draws you in, something that makes you feel seen or resonates with you, gives you some kind of connection with the subject matter.”

Luxembourg.

Harvard University, Collection Development Department. Widener Library. HCL, W555087_1

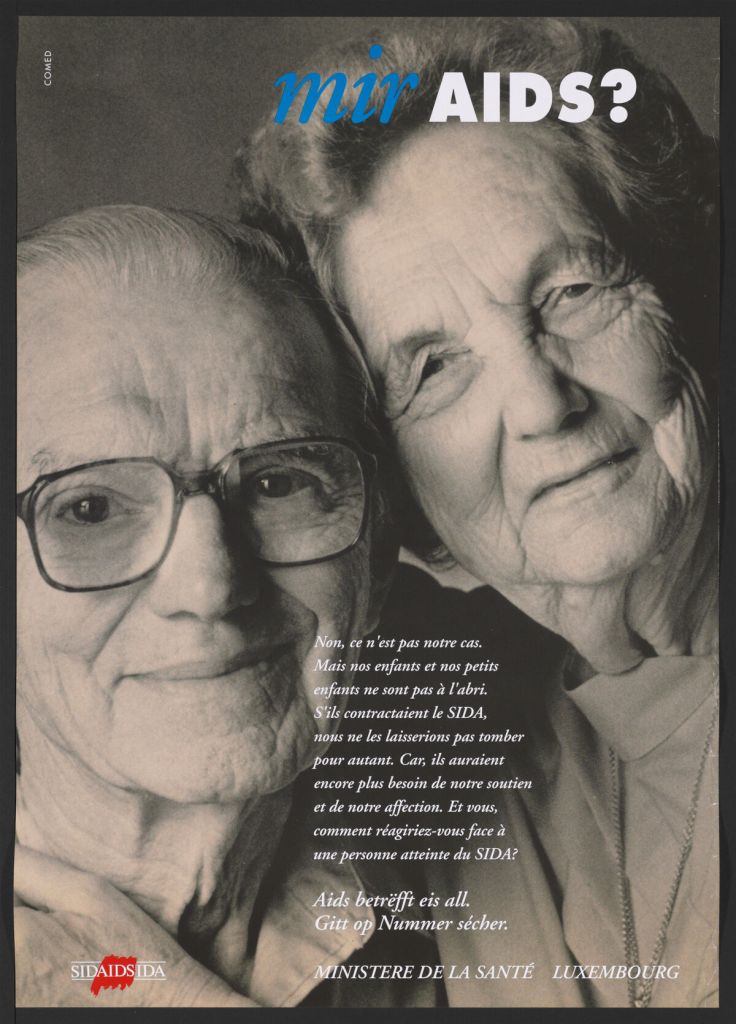

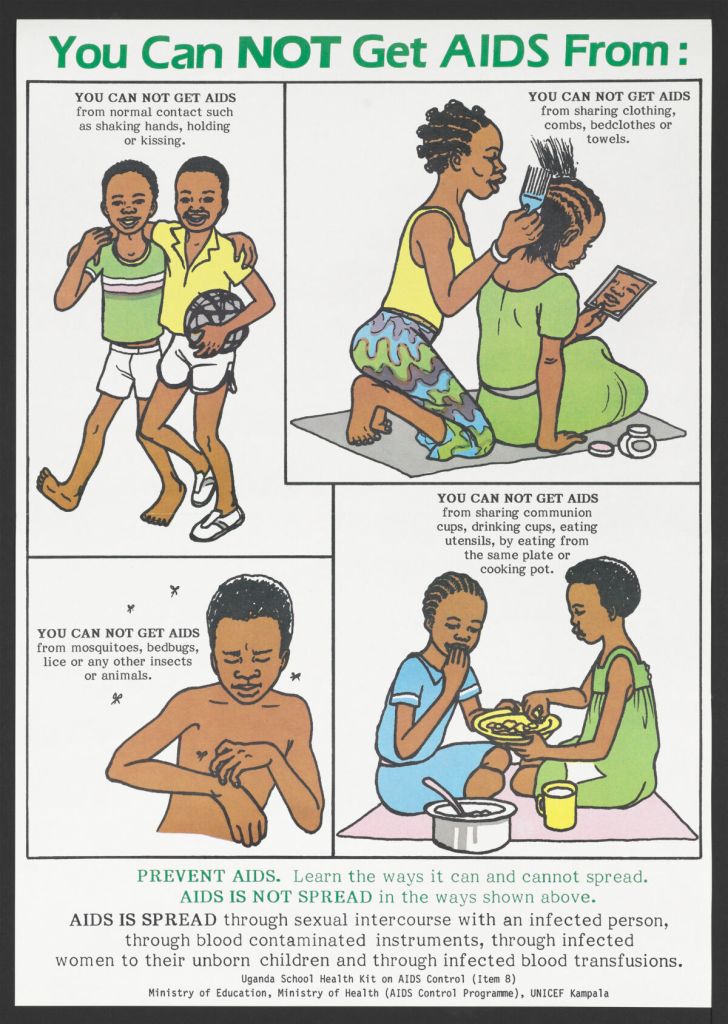

Audience matters

“Often in the early days, there was a single campaign with a single message that was used in every situation,” Yarnell said. “Over time, we realized that you need multiple different campaigns for multiple different needs.”

Luxembourg.

Harvard University, Collection Development Department. Widener Library. HCL, W540084_1

Uganda.

Harvard University, Collection Development Department. Widener Library. HCL, W548336_1

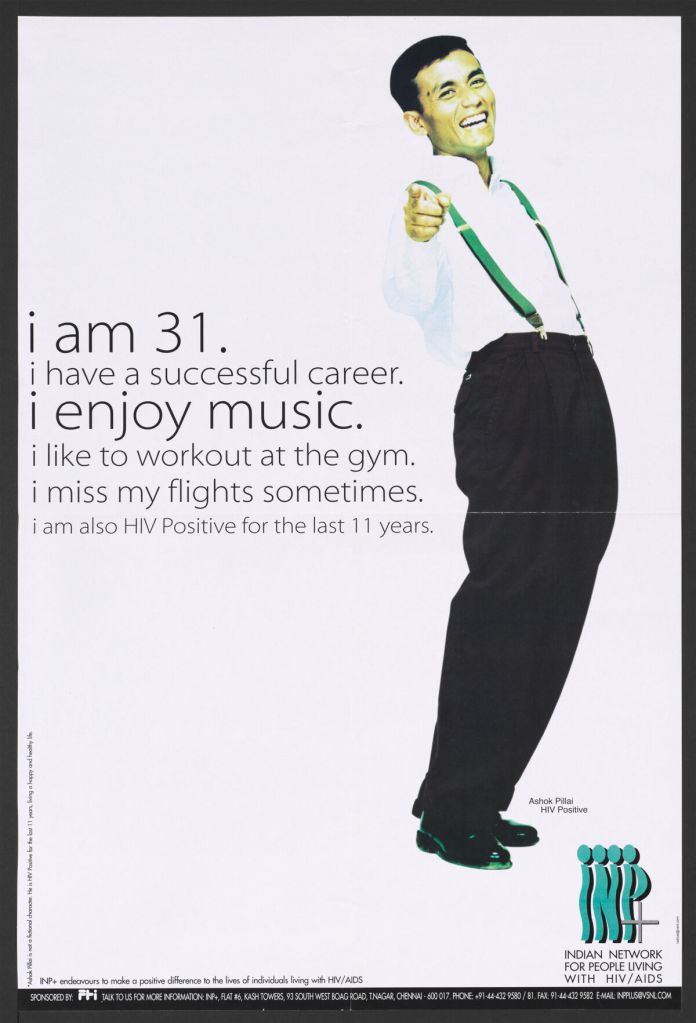

India.

Harvard University, Collection Development Department. Widener Library. HCL, W543116_1

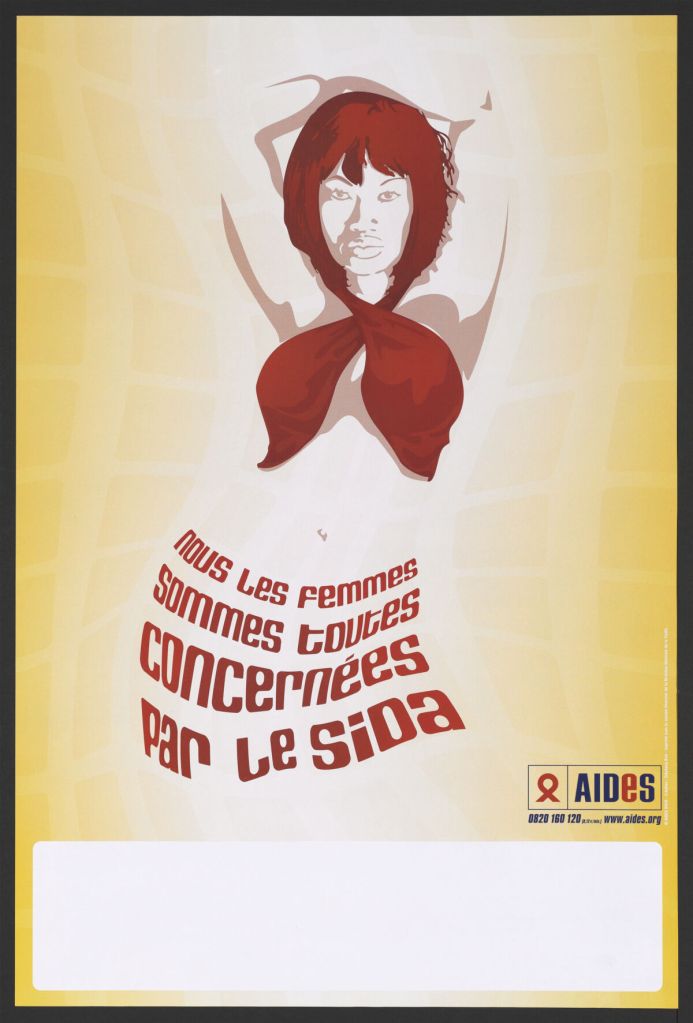

France.

Harvard University, Collection Development Department. Widener Library. HCL, W544068_1

Co-create the message

“For a long time, public health was really focused on, ‘We’ve gathered some expertise and we’re going to share it with you,’ as opposed to ‘We’re going to co-create expertise to help you make better decisions in your life,’” Yarnell said. The best way to make sure the message fits the audience, after all, is to make the audience a part of designing the message.

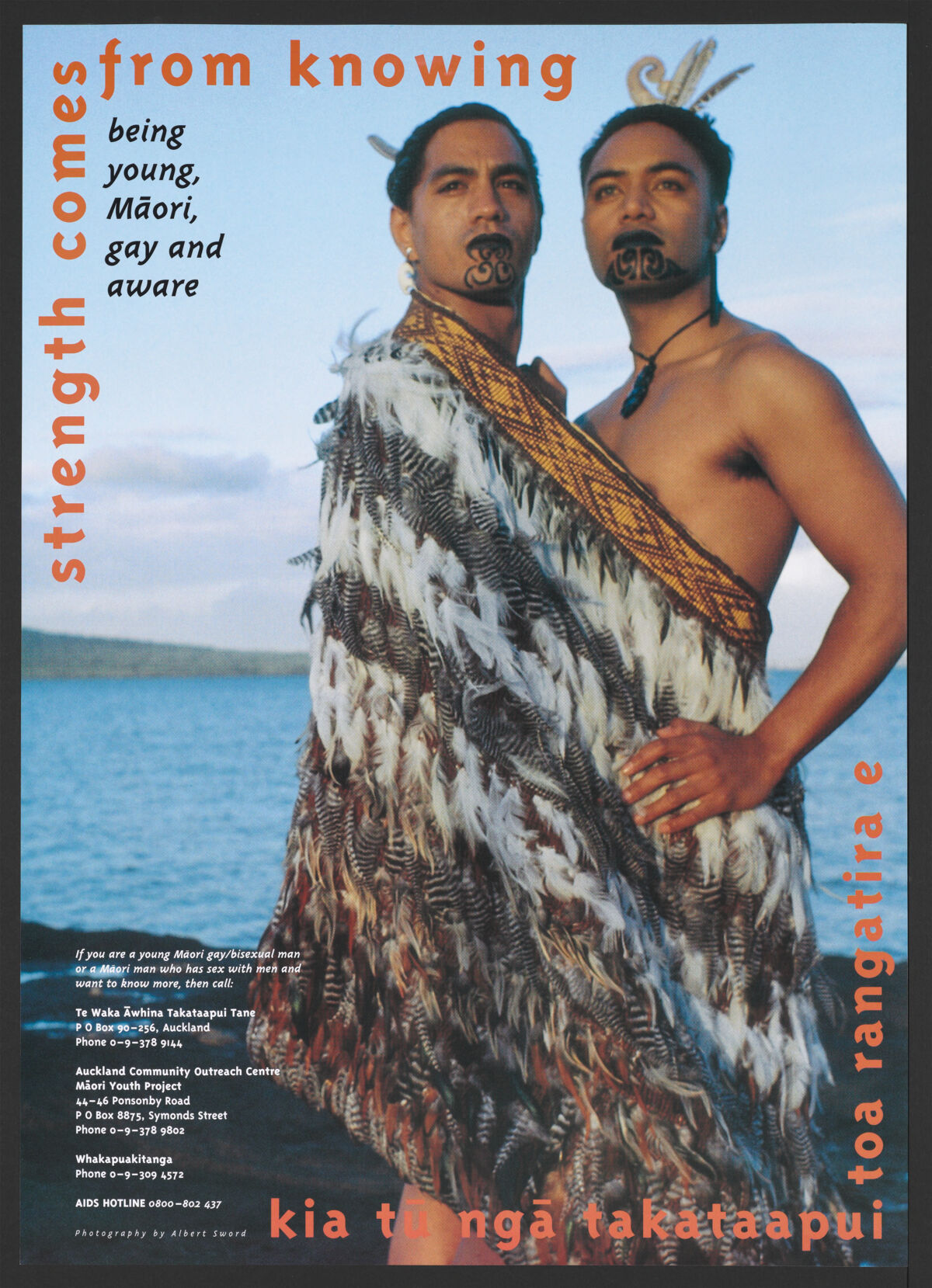

New Zealand.

Harvard University, Collection Development Department. Widener Library. HCL, W547888_1

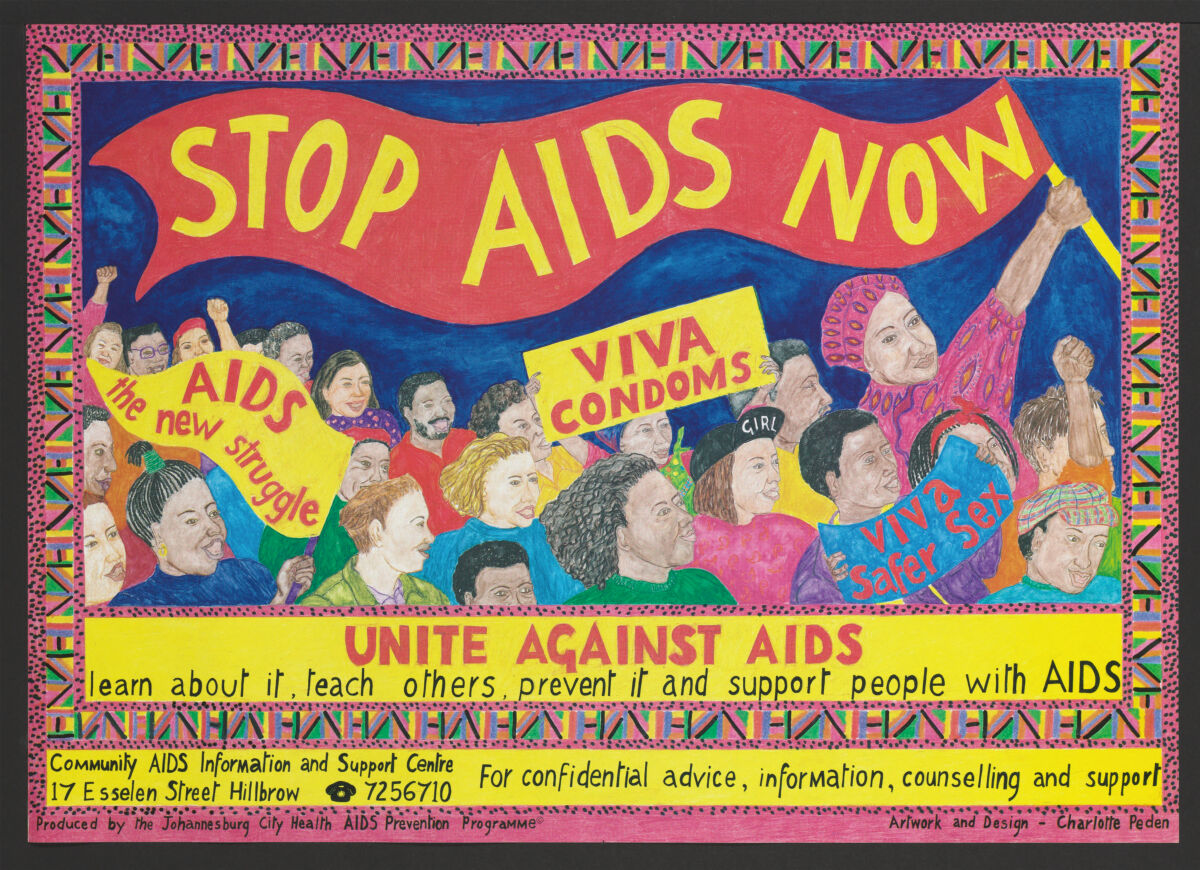

South Africa.

Harvard University, Collection Development Department. Widener Library. HCL, W548280_1

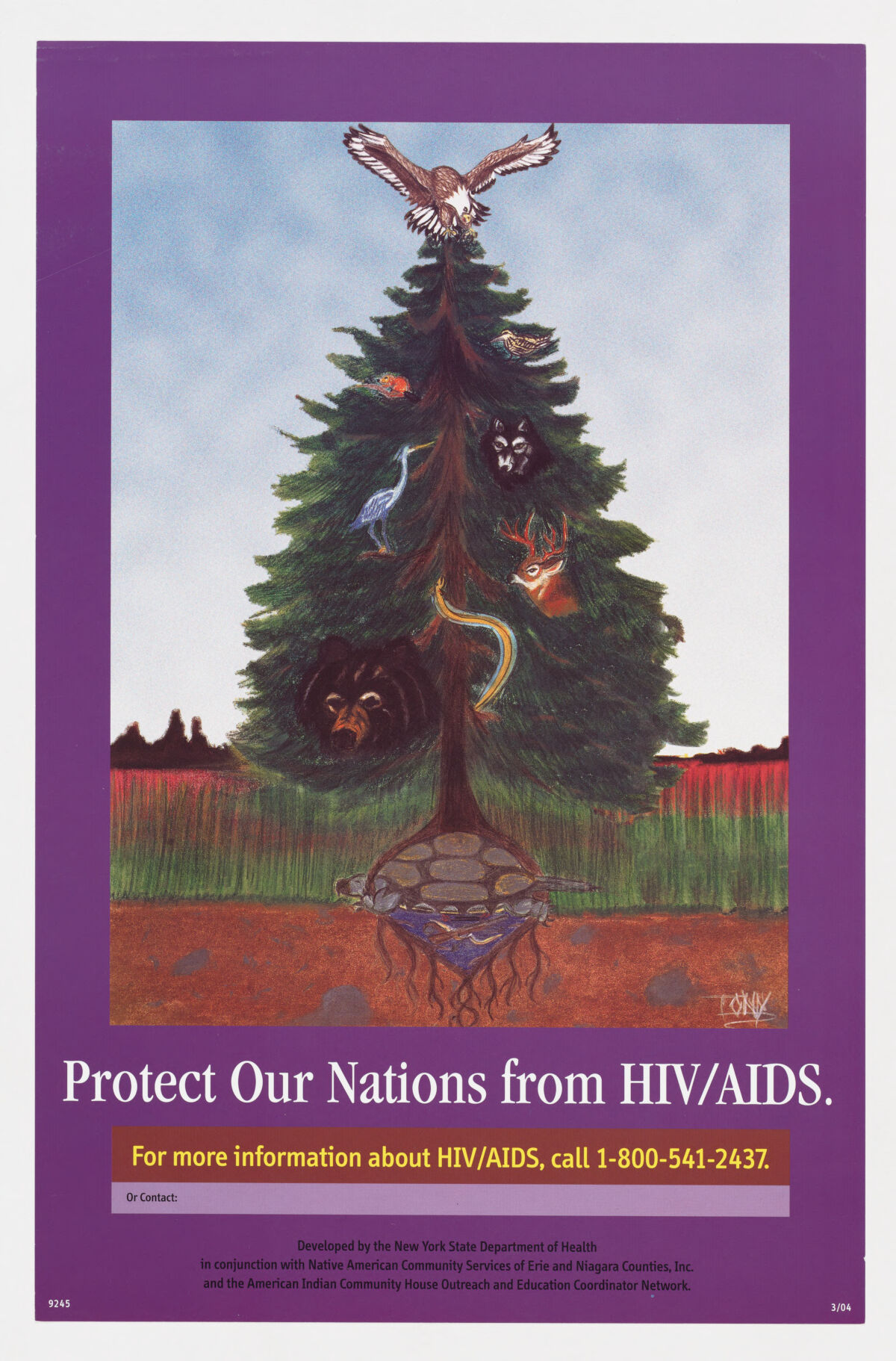

United States.

Harvard University, Collection Development Department. Widener Library. HCL, W463631_1

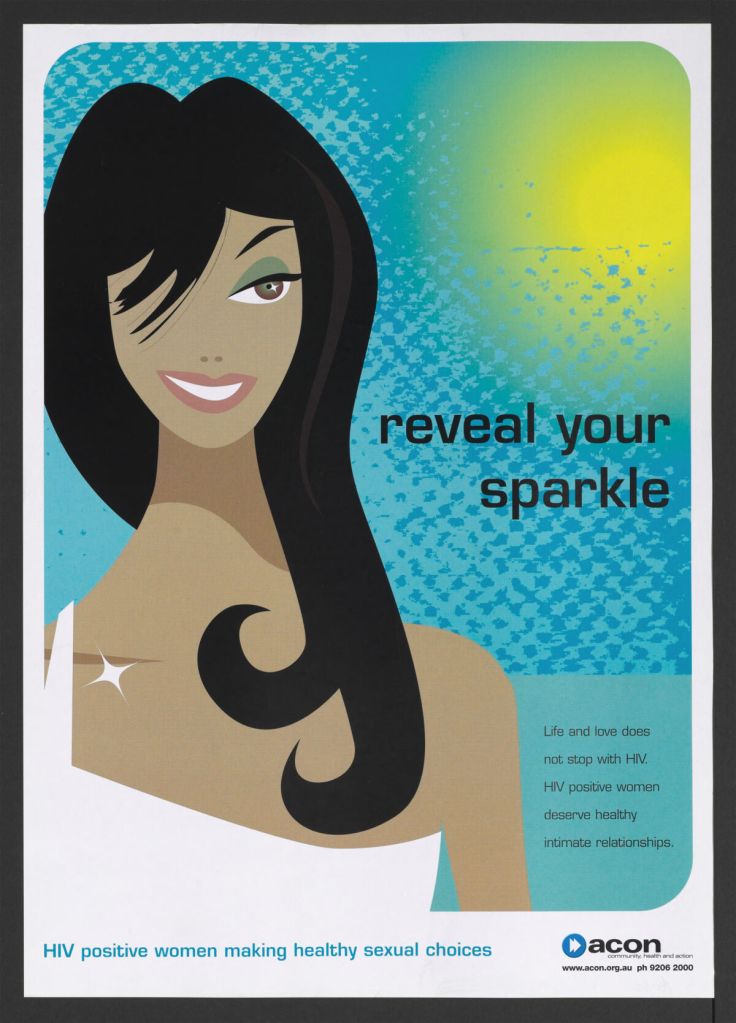

Times have changed

Over time, researchers learned that positive, affirming messages are better for changing behavior than messages based in shame, stigma, or admonition, Yarnell said.

Australia.

Harvard University, Collection Development Department. Widener Library. HCL, W547913_1

Looking back at the posters in the collection is an exercise in remembering the past and preparing for the future, said Neal Baer, lecturer on global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School.

“Condoms were the only things we had to prevent HIV back then. Now, it’s very different. We have PrEP [Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis]; we have antivirals that keep people alive. … These posters are outdated in the sense of the information they’re giving out.”

It is estimated that about 42 million people worldwide have died from HIV/AIDS since the virus first emerged in the 1980s. With modern preventions and treatments, it is possible to end transmission and prevent deaths, Baer said.

“We haven’t done a good job of preventing HIV transmission in the United States, especially since we have the ability to prevent it completely through ‘U=U,’” Baer said, referencing the “undetectable equals untransmittable” messaging strategy begun in 2016 aimed at changing the conversation around HIV/AIDS. “There should be no one getting HIV.

“This poster collection reaffirms that we need to not forget. … These posters are like gravestones of all the people who have died, and I don’t want them to have died in vain.”

Source link